"Wuthering Heights"

My thoughts on Emerald Fennell's new movie

There are some film version of classic novels that feel designed to appeal to those who know and love the book. Fidelity is the watchword. Generally speaking, most Jane Austen adaptations fall into this category - if with the occasional added touch such as Darcy’s wet shirt. The superb versions of modern classics such as Remains of the Day, The English Patient and Atonement are also super-true to both the spirit and the letter of the book.

Then there are films that feel designed to appeal to those who have never read the book, but because the filmmaker is so passionate about the book they want to create a shared passion in the viewer and they will go to any length to do that, both to fulfill their own dream of creating a companion work purely in the spirit of the book and in the hope that they will inspire the audience - especially the youthful (Gen Z) - to try the book for themselves. Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” falls firmly into this category, as witnessed by the quotation marks around its title in the opening credits, and as such it is a triumph.

I went with very low expectations, having read some blistering reviews, including the Times saying that “Margot Robbie is a Brontë Barbie” and one by my old Cambridge contemporary Pete Bradshaw, whose judgment is usually impeccable. There was further apprehension when I looked around the lovely little screening room in Chipping Norton and saw that I was the only male in the auditorium. Hm, I thought, should I have given it a pass (as Jeremy Clarkson and David Cameron seem to have done) and allowed Paula Byrne, as fanatical a Brontëite as she is a Janeite, to go alone? Unsurprisingly, as we walked out, there was many a muttering from Generation Chippy: “It wasn’t very like the book.” I turned to Dr Byrne and before I could speak she said “I loved it.” This didn’t surprise me: after all, she is one of the world’s leading Austen experts but, as she told Amy Heckerling in a recent radio show, her favourite movie adaptation is Clueless, so she totally gets the idea of the “spirit” as opposed to the “letter” of the original.

But the real surprise was that I loved it too.

Here’s why, in just a few words. The costumes (though, as in most adaptations, they were resolutely Victorian, or post-modern reboot of Victorian, despite the fact that the first word of the novel is “1801,” indicating that the events take place between the 1770s and the end of the eighteenth century). The colours: Cathy wearing red, red, red. The raw acknowledgment of the proximity of sexual passion to violence - cf. Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, of whom more in a moment. The rendering of the two houses, especially the over-the-top decor of the Linton residence (boast: in my O Level essay 100 years ago, I got 100% for my essay on why one of the absolute keys to the novel is the contrast between the architecture and interiors of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange … crikey, how I loved the novel when I was a teenager, so much that I dared not re-read it for about 40 years for fear that it would not live up to my memory of it, though when I finally did so, it did).

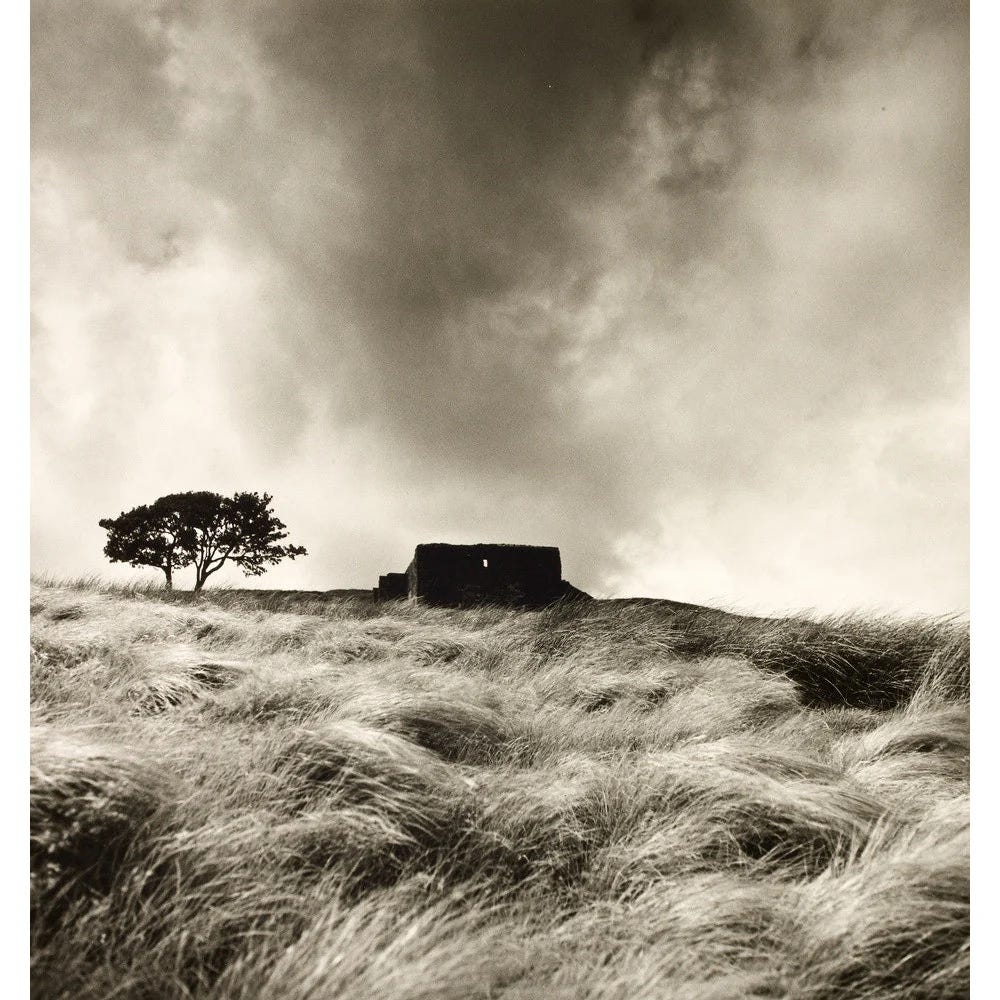

Then there was the stark beauty of the Moors, of course: I was pleased to read that Ozzie actor Jacob Elordi developed his (excellent) Yorkshire accent by listening to recordings of my beloved Ted Hughes. On which note, I loved the moment when Cathy was on a branch in the bare tree, a clear allusion to Sylvia Plath’s and Ted Hughes’s paired poems “Wuthering Heights” and in particular to a (lost, alas) photograph that Ted took of Sylvia on the branch of a sycamore outside Top Withens:

You breathed it all in

With jealous, emulous sniffings. Weren’t you

Twice as ambitious as Emily? Odd

To watch you, such a brisk pendant

Of your globe-circling aspirations,

Among those burned-out, worn-out remains

Of failed efforts, failed hopes—

Iron beliefs, iron necessities,

Iron bondage, already

Crumbling back to the wild stone.

You perched

In one of the two trees

Just where the snapshot shows you.

Doing as Emily never did. You

Had all the liberties, having life.

The future had invested in you—

As you might say of a jewel

So brilliantly faceted, refracting

Every tint, where Emily had stared

Like a dying prisoner.

And a poem unfurled from you

Like a loose frond of hair from your nape

To be clipped and kept in a book. What would stern

Dour Emily have made of your frisky glances

And your huge hope? Your huge

Mortgage of hope. The moor-wind

Came with its empty eyes to look at you.

© The Estate of Ted Hughes, from Birthday Letters (Faber & Faber, 1998)

Ah yes, “the moor-wind”: has any movie ever used the wind machine to such effect? Or maybe it was the real Yorkshire wind on location. The billowing veil on the wedding dress walk across the moor …

On the subject of literary allusions - it was obvious from the Brideshead revisioning that was Saltburn that Fennell has an English degree from Oxford - I also liked the way in which Isabella laboriously spelt out the plot of Romeo and Juliet and then, when it seemed that Cathy was dead and Heathcliff’s arrival too late, Fennell followed in the tradition of David Garrick’s and Baz Luhrmann’s alteration of the ending of that other iconic love story: as their Juliet wakes for a farewell to Romeo that is not in the original Shakespearean text, so C + H have their moment.

I could go on about the many things I loved - the framing of almost every shot (those leeches on the wall!), but the critic in me must also speak. Two omissions bugged me. One was the absence of the odious Hindley Earnshaw. The bad brother is a much more effective device than the harsh father. Putting the reduction of Heathcliff to the status of a servant onto the father who has adopted him just felt wrong. While on the subject of the adoption of Heathcliff, I should say that I disagree with the complainants who wanted casting of his role to go to an actor with a Black skin, as in the rather interesting 2011 movie version. The first description of his appearance, from Lockwood (who, though imperfect, is the most reliable witness we have in the book), is that Heathcliff has a “gypsy” appearance. I’ve always seen his mysterious origin as Romany, or possibly what at the time was called “Black Irish”, or conceivably “Lascar” from the East Indies. Despite the Liverpudlian location, I don’t see hints of the vile transatlantic trade. But I have sometimes wondered whether he is really Earnshaw’s illegitimate son, conceived on some previous visit to the city, and thus Cathy’s half-brother, which would introduce a strong and transgressive incest motif. The film, by the way, was especially good at conveying the childhood bond between the two of them.

The second omission was to my mind inexplicable. Why, O why, did Fennell omit the greatest speech in the novel? I’m thinking of the key scene with Nelly, the pivot of the plot because it causes Heathcliff to leave Wuthering Heights: the conversation in which Heathcliff overhears what he cannot bear to hear and leaves before Cathy expresses her true feelings. It would have worked so well to include the speech in full, so let me end with those words, which also haunted Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath:

I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of my creation, if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning: my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger. I should not seem a part of it. - My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath - a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff - he’s always, always in my mind - not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself - but, as my own being.

In my review I didn't end up loving the movie like you did (maybe it's because everyone at my showing was laughing the whole time), but I love the parallel you draw between the tree scene in the movie and Plath and Hughes' poems! I never hear anyone really talk about those poems in relation to Brontë's novel but they're so wonderful, especially (to me) Plath's. And I was also expecting to hear Cathy's full beautiful speech and was so disappointed when it wasn't included.

Interesting analysis